Absence management is always important, and the cost of allowing absences from work to go unchecked is huge.

As managers will know, the direct cost of absences comes in lost productivity: staff who are absent aren’t working – and even if other staff can pick up some of the slack, you’re not going to sustain normal levels of productivity for long. An estimated £18 billion is lost every year in the UK alone due to absence-related falls in productivity.

You’ll also lose time finding cover, adjusting the rota, holding return-to-work meetings, and carrying out disciplinary processes (if necessary).

It’s then no surprise that absence from work is seen as a Bad Thing That Must Be Stopped.

What is absence management?

Traditionally, absence management aims to:

- Reduce the number of absences

- Reduce their cost

- Maximise the number of shifts an employee shows up for

Today, absence management should be more nuanced. It should consider the reasons behind absences, and work to deal with the underlying causes. Why IS an employee calling in sick to work? Absence management should encourage staff to take sickness absences when they need to while tackling false sickness and unauthorised absences.

Overall, absence management should be concerned with reducing costs in the long term, not the short term. Look at the cause, not the effect.

We’d argue that absence management is best viewed as an extension of a well-being policy instead of the cost-saving exercise it’s often seen as.

Why is absence management important?

Absence management helps you to adhere to your sickness policy and minimise disruptions. By tracking employees' absence from work, you can improve your team's well-being and find and address the root causes.

If done effectively and efficiently, you increase morale and create a supportive environment - with reduced costs and a boost in productivity as a happy side effect.

Types of absence

Before we get into policies and best practices, let’s just clarify what types of absence we’re referring to.

What we're talking about:

- Short-term sickness. This refers to sickness absence of less than four weeks, such as short absences due to mild to moderate illnesses, stress and other mild-to-moderate mental health issues, and injuries that prevent the employee from working.

- Long-term sickness. Sickness is generally referred to as long-term if the employee is continuously absent for at least a month. This can be due to serious illnesses or injuries, worsening of chronic health conditions, or recovery after an operation.

- Unauthorised absences and lateness. Staff going AWOL, even if it’s only for the first 30 minutes of their shift, is a big problem. These types of absences often become disciplinary issues.

Generally, you’ll need separate policies covering each of these types of absence, but cultural changes can impact all three.

What we’re NOT talking about:

- Authorised absences (other than sickness). Maternity and paternity leave, annual leave, compassionate leave, bank holidays and other types of leave are usually covered by different policies.

Absence management policies and best practices

You should draft your absence management policies based on your company’s specific circumstances, and with the help of an HR expert, but here we’ll quickly run through some important points to think about.

Short-term sickness

- Return-to-work interviews.

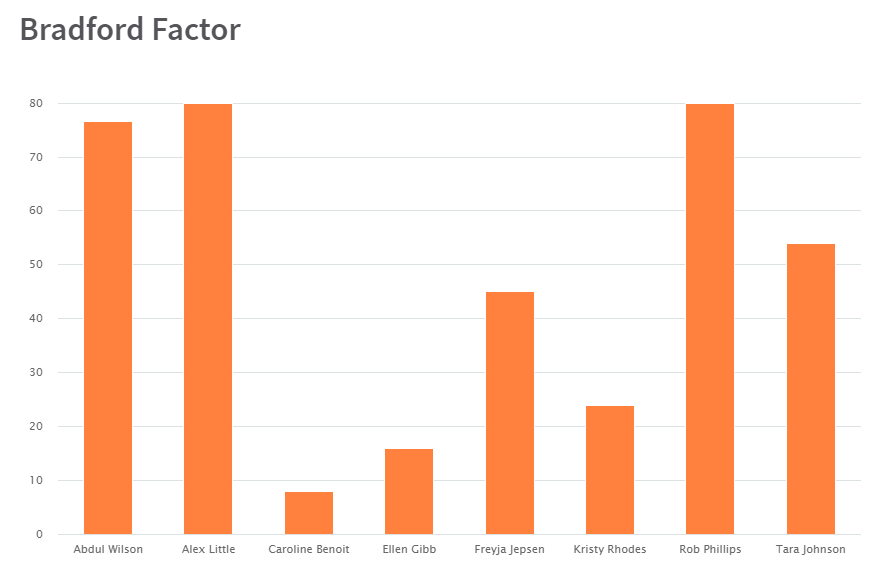

The focus of these interviews should be identifying if there’s an underlying problem that caused the absence and, if it relates to work, putting a plan in place to reduce related instances of absence in the future. Return-to-work interviews also deter staff from pulling sickies, but remember it’s best not to throw around any accusations of unjustified absence in this interview unless you’ve got the evidence to back it up! - Use attendance metrics.

Absence metrics such as the Bradford Factor (which looks at the number and length of sickness absences) are often used to automatically trigger disciplinary action when a certain threshold is reached. However, the numbers don’t always tell the full story. Instead, we recommend using these metrics as a starting point in a conversation before deciding to take disciplinary action. Just make sure your staff know what your policy is on these metrics, and when actions (or processes) are triggered. - Implement an employee assistance programme (EAP).

EAPs offer employees support with personal and work-related problems that may be affecting their engagement, performance or attendance levels at work. EAPs usually come at a very low cost, and even a modest take-up can reduce absences. - Train managers.

Line managers should know your absence management policies inside-out, understand how disciplinary processes work, know when employees require fit notes, how to talk about difficult and sensitive issues, how to run return-to-work interviews, how to record absences and track metrics, and so on. Managers should also be involved in building and maintaining a working culture that values employee health and wellbeing, so you can reduce the absences caused by stress and other workplace-related ailments. - Speak to occupational health experts.

They can help you understand the current issues with absence management on your team, and also carry out risk assessments to identify problems which you may otherwise have missed. - Be more flexible.

Provide leave for medical appointments, family emergencies, and other unforeseen circumstances. Offering flexitime or working-from-home benefits also gives your staff more flexibility and may reduce the number of sick days they need to take. But make sure staff take time off when they need it!

Long-term sickness

Many of the points made above apply to preventing long-term sickness, too. However, the big difference here is that returning to work after a long absence is often very difficult.

- Keep in contact.

When it’s clear that any sickness absence is going to be long-term, reach out to the employee and establish how and when to stay in contact. For example, an employee recovering from an operation may want a phone call every week or so, whereas an employee struggling with mental health may prefer an email once every couple of weeks. These communications should be about employee welfare, not nagging them back to work. They also give you a chance to keep the absent employee up to date on the goings-on at work, and start talking about the adjustments they might need once they’re well enough to return to work. - Build a return-to-work plan.

It should take into account advice from the employee’s doctor or an occupational health professional, and cover things like whether the employee’s return will be phased, any reasonable adjustments to working patterns and working environments, and when their return to work will be reviewed. - Be aware of discrimination.

Make sure HR and managers alike know if the employee’s injury or illness counts as a disability under the Equality Act, as this can affect disciplinary action and may lead to costly employment tribunals.

Lateness and unauthorised absence

- Establish expectations of ‘acceptable’ vs ‘unacceptable’ absence and lateness.

Some staff might regularly turn up late because they know specific managers will be indifferent to it. Or, you might be OK with staff turning up ten minutes late for quieter shifts, or because of a one-off problem with their commute. Make sure all staff and all managers understand what counts as lateness for disciplinary and record-keeping purposes, and make sure managers apply these rules consistently. - Explain the impact of unauthorised absence and lateness.

Some staff may feel it’s no big deal to miss a shift or be consistently late, but if it has an impact on the business, either directly or indirectly, you need to communicate this to them. For example, you may take less revenue when you’re an employee down, or you need your senior employees to set a good example to new employees, who may be unclear about the expectations around attendance and lateness. - Start with an informal discussion before issuing warnings.

long-termA quick chat with no mention of disciplinary procedure may help you get to the root of the problem and understand why an employee is consistently late or missing shifts. If you find they have caring responsibilities, have been struggling with illness, or something similar, be lenient about their lateness. Hinting at disciplinary action isn’t going to achieve much, and may even make the problem worse.

Fixing presenteeism and leaveism

The other side of absence management is when employees aren’t taking sickness absence when they need to. Enter two isms: presenteeism, and leaveism.

What is presenteeism?

Presenteeism is when staff show up for work when they’re sick because they either can’t afford to take time off or feel pressured to work even when not at their best.

It’s becoming a big problem. We’ve seen the number of sick days staff take fall sharply – and it’s not because we’re getting healthier.

What is leaveism?

Leaveism (or leavism) describes the practice of staff taking annual leave (or using other work benefits) to take time off when they are unwell, or they continue to work even when they’re on annual leave. This relatively new term combines four different work practices which obscure the true amount of sickness taken by staff.

These practices can be incredibly damaging for employees’ health, but some staff feel they have no choice but to use annual leave or work from home when ill because of the disciplinary or cultural cost of taking sickness.

This is the type of practice that might make your absence management stats look good, but is actually having a harmful effect on your employees and your business. Annual leave is meant to be used as leisure time. Lying in bed with a fever or the flu isn’t leisurely.

Frequently asked questions

Skip to:

How many sick days per year is acceptable in the UK?

What if I don’t think an absence is genuine?

In RotaCloud

RotaCloud includes many HR tools to help you record and manage absences effectively.

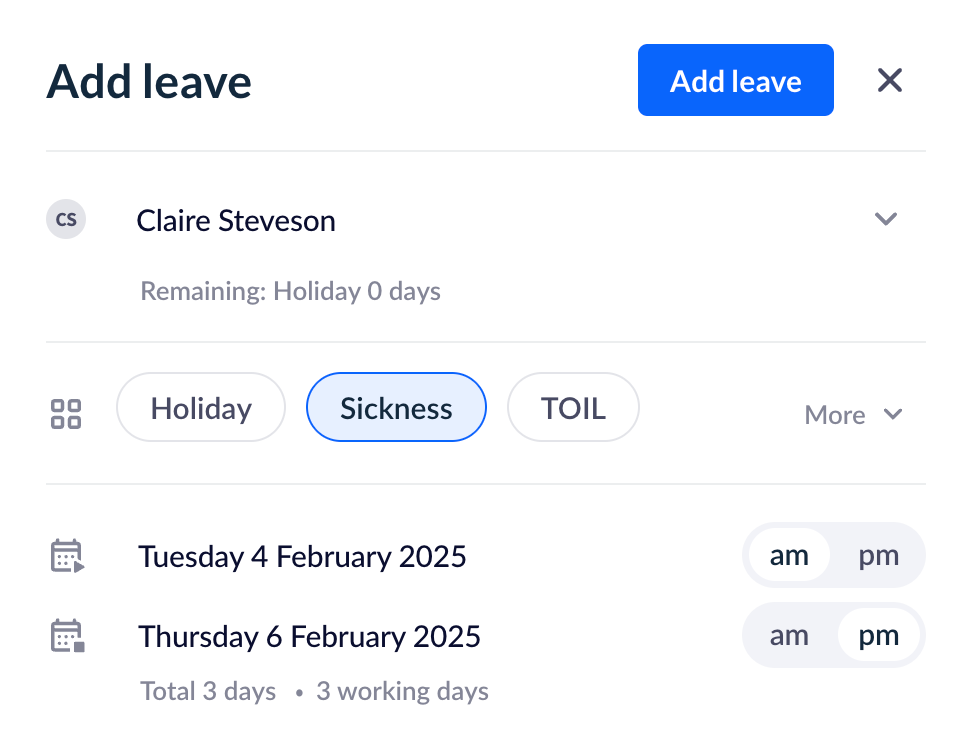

The first stage of absence management is measurement — and you can’t measure absences if the records you hold are messy, incomplete, or difficult to collate. In RotaCloud, you can add periods of sickness in the same way as every other kind of leave.

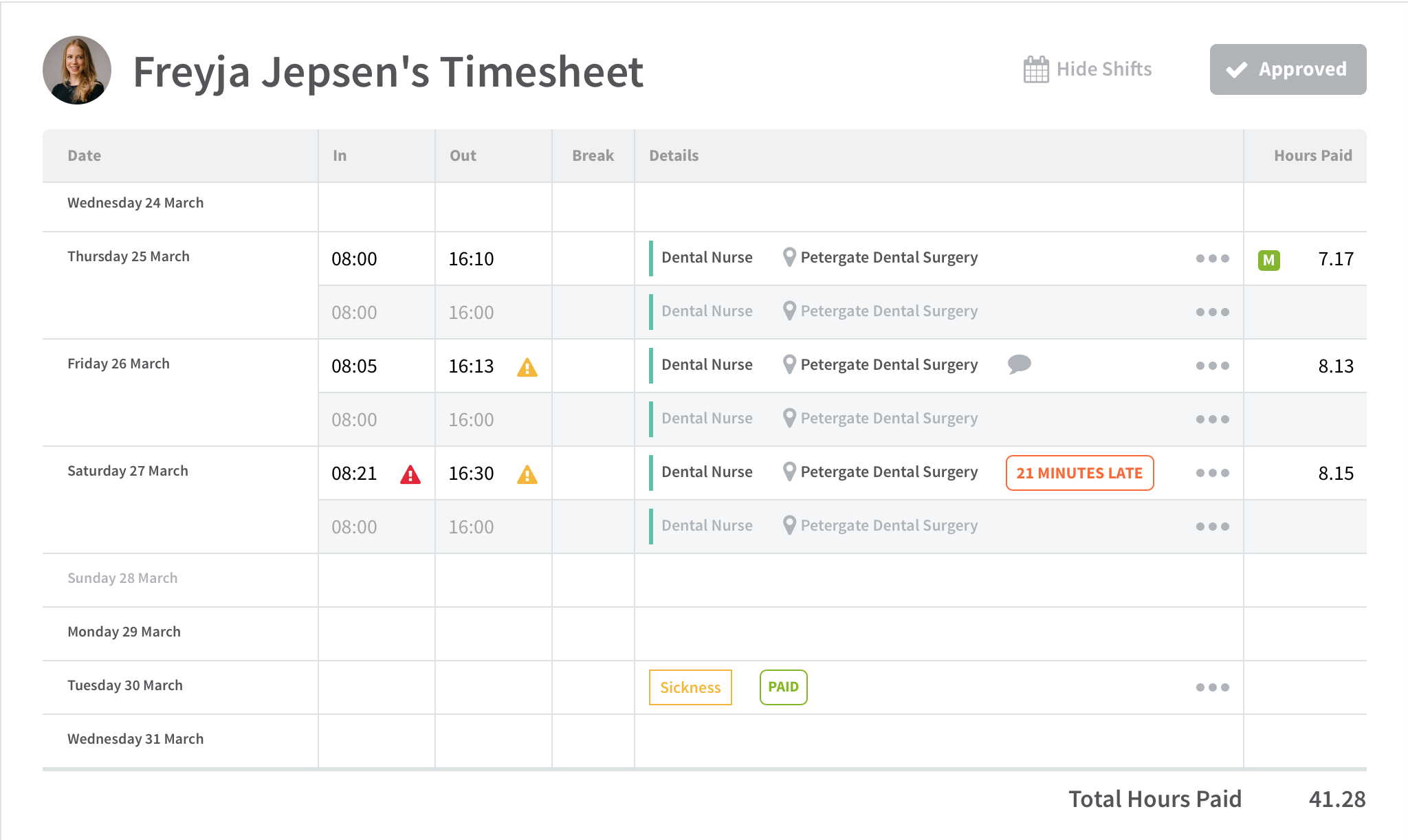

Staff can clock in and out of their shifts using the RotaCloud mobile app, with GPS or IP restrictions, or a static terminal at their place of work. Data is automatically fed through to employee timesheets, with instances of lateness flagged, providing full visibility to managers.

You can also use RotaCloud’s built-in reports to identify sickness and lateness problems across your teams. For example. there’s the Bradford Factor report, which instantly shows you the Bradford Factor scores of your staff.

Wrap-up

Your absence management policies need to strike the right balance between deterring false sickness absences and lateness, and making sure your staff take absences when they need them. Discouraging staff from taking sick days under the guise of saving money is only likely to cost you money in the long run when taking into account issues like presenteeism and leaveism.

But remember, your policies are only as effective as the managers who enforce them. Making sure everyone’s on the same page is the best way of reforming absence management at your business.

Read next ➤

“It does my holiday, it does my reporting, it does my Bradford factor for absence; it does a multitude of things very, very easily in one simple system.”

See how Belmont Healthcare dropped their agency cost from £10K to £720 and reduced last-minute sickness calls thanks to RotaCloud’s Absence Management, Unavailability, and Shift Swap features.

How many sick days per year is acceptable in the UK?

The ‘acceptable’ number of sick days varies from business to business and team to team. In terms of average numbers, we found that employees took only 3.4 days of sick leave in 2020, while the ONS reported 4.2 days in 2019. However, back in 1993, it was at 7.2 days! The frequency and length of any absences can also change the ‘acceptability’ of any absence. For example, the Bradford Factor metric counts shorter, more frequent periods of absence as more disruptive than longer, less frequent absences. So a 10-day period of absence may be acceptable, while 10 separate single-day absences may not be.

What if I don’t think an absence is genuine?

If you have clear evidence that a sickness absence wasn’t genuine (such as a social media post where the employee’s at a pub watching a football match that was on when they were sick), clearly you’ll need to take disciplinary action. However, if you’re not 100% sure, carry out further investigations. You can ask them about the reasons for their absence at the return-to-work meeting, and take note of any discrepancies. And remember, staff should have doctors’ notes for absences of more than seven days.

Can I dismiss someone for sickness absence?

Yes — either under your disciplinary processes or if an employee is no longer capable of performing their job duties. However, make sure you have plenty of evidence to back up your decision — and if the employee has a disability (under the Equality Act), you must make sure you’ve made reasonable adjustments and exhausted all other avenues before proceeding (and of course, speak an employment law expert — this article isn’t legal advice).

How can I measure absence?

There are a few different metrics you can use. The most common (and controversial) is the Bradford Factor. It takes into account both frequency and length of absences.

There’s also the ‘lost time’ rate, which is worked out by dividing the total absence (in hours or days) by the total hours or days in that time period, and converting it into a percentage.

For example, if a team of three had nine days of sickness over a 30-day period, you’d divide 9 by 90 (the total days of work across the three employees), you’d have a lost time rate of 10%. You can calculate this rate per employee, team, or across the entire business.

If the frequency of absences, rather than the overall time lost, is your main concern, you can calculate a frequency rate. Here, a one-day absence counts the same as a five-day absence. Simply divide the number of spells of absence by the number of employees, and convert to a percentage. E.g. a group of 10 employees had five spells of absence over a certain period. The frequency rate is 50%. This metric is also useful for comparing absence across teams.

Editor's Note: This post was originally published in April 2021 and updated for accuracy in February 2025.